Picturing people on the walk

With the days having gotten so much shorter I am now virtually always up before the sun and going down long after it. Compressing the same rhythm of walking into dramatically fewer hours is partly to blame for the much reduced communications, but I’m also leaning into that freedom to only update once a week or so, in order to give shape to these bigger essays.

The other upside to the shortened day is never missing the morning golden hour, where the sun makes the whole world a shimmering wonderland (so long as the skies are clear, anyway).

In Idrija, Slovenia, on a cold morning as I passed through the square on the way to the library I saw a woman lent heavily on a table under an awning, smoking a cigarette. We were the only people about and the library wasn’t open yet, so I stopped and sat at a bench.

As she made to leave I asked if I could take her photo, I wanted to capture that quiet, brooding figure. She laughed and said “me? you are welcome” in a heavy accent, giving a little flourish with her hand. By then she had reached an archway at the edge of the square. I took a photo, we said hello, we said goodbye.

But the woman in the photograph is not the figure that had been leaning under the awning just a moment before.

She had made no error, if there was error it was mine; I had watched the moment pass. Even if I had asked her before, while she still lent on the table, I would have interrupted the very moment I wanted to inhabit. It’s just one of the facts of the craft. But, for all its hurried fault, and despite not capturing anything of the character I had seen, I like the photo, and I’m glad that I asked, not least because it prompted me to revisit my attitude to taking photos of people.

The beauty of photography, of any expressive craft, is being able to reveal what you see, even if only to yourself — to capture the moments.

- 一期一会 ichi-go ichi-e

-

A Japanese idiom which is most often translated as ’for this time only’ and which serves as a reminder that, whether we meet someone often or only once, we will never again encounter them, nor ourselves, as they are in that moment. Every encounter, no matter how mundane, is unique.

Time spent with others is precious, for no moment can ever be repeated, and that truth extends beyond the moments we spend with people, it is true everywhere. Entropy comes for everything and everyone, nothing will ever be the same again. That moment, the scene as I stepped into the square that morning, was gone. Certainly it will linger in my memory for a while, but a memory is not the moment it remembers. Even the best photograph is only a proxy for the moment it wished to remember. The better images do at least edge a little closer to the moment though.

A good friend, Paul, has all but stopped taking photographs. He has a great eye for it, used to carry the same kilos of glass, metal, and plastic into the mountains that I do, but at some point he decided he’d taken enough proxies.

The ready frustration of photography is that every single frame is a failure. If you’re trying to faithfully convey a scene, a place in time, an emotion, anything specific at all, then every frame falls short — the only variable is the degree of that failure. There’s nothing peculiar to photography in that, it’s true of every craft: The Platonic ideal is never achieved, never seen front on, it teases us, ever in our periphery, gone just as soon as we try and capture it. It would be impossible even to estimate how many times I have missed a frame, or given up on a piece of writing, or never bothered to try — knowing what the outcome will be. But practice, praxis, craft, graft, The Work, whatever you call it — that is the goal. Yes the form matters, and yes, every effort is an imitation far outside the Realm of the Forms, but meaning is made in the attempt, nowhere else.

Sometimes I come back to a piece of writing — or return to a feeling I tried to frame — and I get a little closer and, increasingly, that’s enough. Every time I pick up the pen, or the camera, or take another step to the East, I practice being satisfied with getting just a little closer.

Paul is in the Brenta region of the Dolomites now, a week and half of roped excursions over the peaks and, secretly, I hope that he takes a photo or two.

I very nearly joined him but our schedules were a few weeks out.

Looking closely at people

And the murky ethics of it.

After the photo in the square, I spent a lot of time thinking about the kind of images I want to put into the world. In writing about why I’m walking I touched on some of the ways my relationship with the world has changed over the last handful of years, how it centres people in a way that it never did before I ‘ran away’. But I feel that my nascent creativity hasn’t kept up with that growth; my writing, my photography, in many ways both are just a whole lot of navel gazing.

I don’t mean to give up the navel gazing, that activity is core for me, it brought on the change that I’m talking about, it drives me to walk, and in almost everything else that I do, but I want my work to reflect all of the things that matter to me and so, I want people to feature more heavily in these artefacts (words, images, drawings) that I’m increasingly driven to produce.

With the exception of friends, family and partners, I’ve generally steered clear of candid photography. There are several reasons for that, but in the main they fall into two categories: anxiety and ethics.

My anxieties about taking pictures of people can be reduced to The Ask and The Witness.

To ask is to invite rejection. I don’t fear rejection like I used to, my remaining discomfort as far as rejection is concerned has to do with the difficulty in knowing with certainty that someone feels able to answer truthfully, to say no if they want to. I’ll explore this more in the ethics section below.

As for The Witness, by that I mean: if taking a photograph of someone (with permission), they see you in your work. If you fail, if the photo is crap/unimaginative/unflattering, they stand witness to that failure, they make it larger, amplifying a feeling of having wasted their time. And if taking a candid photograph, then there is the risk of ‘discovery’. The person turns unexpectedly and sees you, and your camera, seeing them, what then? How does that experience make them feel?

With anxiety being less and less a part of my life, it is my unresolved feelings about the ethics of taking pictures of people, in almost any context, that stalls me most. Pesky ethics, always getting in the way of a good time! ;)

Broadly speaking, I think the ethical dilemma can also be divided two ways: a photograph can be taken either with permission, or without permission.

Taking photos with permission would seem pretty straightforward, right? If you’ve asked someone for permission to take their photograph, and they say yes, what could be wrong with that? Well, did they feel able to say no? Could they have felt intimidated? I’m a fairly thin guy, I don’t have an abundance of visible (or non-visible) muscle, I wear a brightly coloured shirt, a goofy hat, and a big smile wherever I go, I make conscious effort to be less intimidating in order to better connect with people that I meet; but I’m also above average height, a man, I sleep rough, and while I wash in rivers often I haven’t had a shower in a month, I see my face in a mirror barely once a week and sometimes perhaps I look a little rough around the edges; how can I know which appearance is more vivid for any given person I talk to?

Ultimately, I can’t resolve this one. Our every act and movement in the world ripples outward, affecting others, altering their course, this cannot be avoided. I try to minimise the harm I do, and increasingly I am learning how to do more good too. Certainly I will err many times along the way, but I feel that I can no longer justify not doing simply because of the merest possibility of harm.

What of taking photos without permission? Perhaps that is simpler, I mean, surely you just don’t do it? But wouldn’t that rid the world of so much incredible art? And not just art but cultural memory, images that allow us to believe that history actually happened.

In 1930, nearly twelve years after the end of the First World War, ‘the world’ was still deciding what Germany’s fate ought to be, to whom reparations were owed, and how much. Erich Salomon was at The Hague and took some of the only photographs that capture that profoundly significant conference of world leaders which put (so far irrevocably) the American banking sector in the driving seat of foreign policy across the Western world, and arguably created the necessary conditions for Hitler’s populist rise and seizure of power less than three years later.

What too of the photographs Execution of Nguyễn Văn Lém (1968) by Eddie Adams, or Napalm Girl by Nick Ut (1972): a picture of a naked child (Kim Phúc) running in terror after a napalm strike destroyed her home. These, along with other such images, taken without permission, meaningfully altered public opinion against the Vietnam War.

I haven’t included either of the two photos just mentioned as it is up to you whether you want to see them, but they are so famous that you have likely seen them already. If you do look them up, try and ask yourself if those photos should exist, I’m curious to know where people stand there.

In literature, the publishing of Anne Frank’s diary could well be considered ethically abhorrent, but is the world not better equipped to reckon with future evils with such an account stitched into our collective being?

Even outside of such extraordinary events, the record of human existence is best captured broadly. It should reflect the extraordinary but also the mundane, the good and the evil, our highs and lows, and everything in between.

If that is true then the permissioned/posed photograph is not enough, it matters, but it is no substitute for the candid one.

There is another rationale (whether it justifies itself I will leave to you) for taking candid photographs.

While some people can pour themselves into the frame, can speak to the camera as themselves, effortlessly, these are enigmas, like those enviable people who can take a hat off in public and have their hair still look good. The rest of us must endure the silent embarrassment of the sweaty birds-nest that spills forth when our hats come off, and likewise, when a camera appears we can’t help but to straighten our hair, our clothes, turn square to the camera, swap our felt expression for our practised smile — and in all that, the character that inspired the photograph has disappeared, replaced all too often with a smiling but perhaps self-conscious shadow.

Only the candid record can capture the candid act.

In a little hamlet in the south of Slovenia I stop at a bus stop to make my regular breakfast, granola in a plastic jar I found in a bin back in Austria. (And which has proven to be the very best plastic jar I’ve ever owned).

Across the road a married couple are putting up walls. He stands on one side of the wall: tall, imposing, slightly stooped by years of labour, hair of pure silver except for a jet black moustache. She is of smaller stature, dramatically so if you account for the bow in his back and knees. Her hair is still black but her face has more creases than his, more worry written into her features.

They’re arguing, they look as though they’ve been arguing for a good bit longer than I’ve been alive. He orders her about, snapping this and that, when she snaps back I give a silent little cheer, but now things have reached an impasse: they both want to use the wheelbarrow. She wants it to collect up all the offcuts that he’s told her to, he wants it to go and get some more blocks for the wall from the pile in the far corner of the garden.

While they argue, he stops and lights a cigarette. With his lungs full of smoke he seems to relax, his shoulders tip back and he manages to straighten his back for a moment. She sees her opportunity and sets about tossing shards and splinters into the barrow. He says nothing for a while, waiting until he’s had enough of his cigarette. He tosses the butt, and then tosses the barrow too, before wheeling it off to the far side of the garden.

They both work hard, probably day after day, but by the looks of it they give half their energy to working against each other. By the time I’m finishing my granola they’ve reached an uneasy truce: he has his stones and she is making piles out of the shards for a time when the wheelbarrow might be yielded unto her.

The work, the care, that he puts into the wall is supreme. I idle a moment longer just to watch as he shapes each stone. First placing the raw stone where he wants it, perhaps rotating it for best fit, then kneeling and, with nothing but a hammer, and entirely by eye, each stone is hewn to the desired proportions, then hauling himself back to standing and settling it into its final place. Again, and again, and again. His infinite care for the wall is contrasted sharply, sadeningly, with his (seeming) lack of care for his partner, his team mate.

Wandering away down a gravel track, two deer bolt at the sound of me. They move completely in sync, both take flight together, up a steep bank, part way up they both pause, again in perfect synchronicity, the clunk of me unclipping the camera sets them both off again and their gone before I can get a clear photo, save for their two retreating bums.

What a contrast, that a pair of animals can be so completely in tune without making a sound to one another, and two people can be so out of tune with an entire spoken language at their disposal.

After I posted this, Joy sent me a message of encouragement, saying that she agreed photos can be taken respectfully without permission, but she added the following:

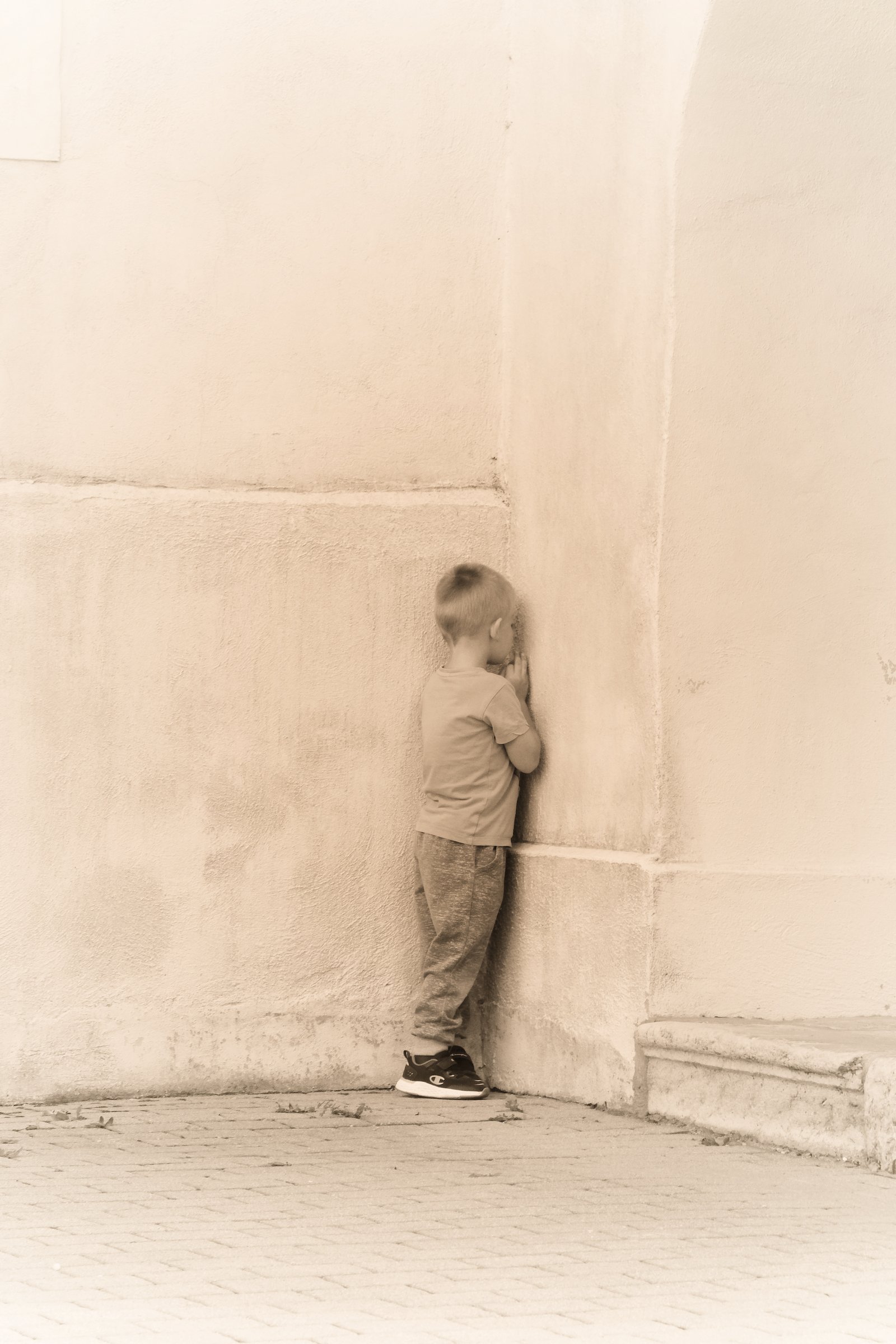

How then do I square my having taken the first of the photos below? I had stopped at a water fountain, near a church in a tiny little town. While I was filling my bottles a man and his grandson came by, the boy begging the man to play hide and seek with him. When the man relented, the boy showed himself to be… not very good at the hiding part. His grandfather had to work quite hard to not find him immediately. I found the scene too pure to turn away from and took a photo of the boy as he pressed his face into a corner of the church, reminded of that time when I too thought that closing my eyes made me invisible.

I reasoned that the child, pressed against a wall as he is, is anonymous, but is that sufficient?

The second image is not so fraught, I wanted to include it simply because I liked the contrast of play and work, young and old, clean and dirty, light and dark.

For now this whole digression into ethics was/is an attempt to capture some of my feelings so that I can continue to revisit them later and see how/if they evolve. It stands both incomplete and unresolved, so I am left to admit that, even in that state of being uncertain re taking photographs of people — candid or otherwise — I have begun to explore it anyway. I welcome your thoughts, particularly if you would criticise my rationale.