The forests of Northland

Chapter 2 of A short walk beneath a long white cloud

In which the heavens open; an Irishman appears; slips are had by all; and friendships emerge.

Day 6 – Rain over Raetea

It rained through the night and in the morning we resumed our weather conference with Joel & Alice who had decided not to venture on just yet, a wise decision no doubt, given the state of Joel’s foot. Kath joined us and she too had decided to wait out the storm, fearing the state the forest might be in she warned us against setting off but Rose and I were hell bent on walking it seemed and began packing our bags. Our things were scattered everywhere having spent all of the previous evening with Joel, Alice, and Kath instead of getting sorted, the curse of good company. Saying goodbye to the gang, we set out under threatening skies and rejoined the road heading toward Raetea forest. Normally, the prospect of trudging along State Highway 1 might have been an unpleasant one but the way was eerily quiet, still closed to traffic following June’s once in 500 year storms and the subsequent slips that had laid waste to the road.

Late morning we caught up to Mitch & Olaf who had stayed the night at the lookout and got a head start on us, we snacked together and a couple hours later we all shared lunch under the cover of Takahue hall, the rain having started half an hour before. As we drew closer to the hills, the dark clouds crowding above them, the rain began in earnest.

Reaching the campground before the forest, Mitch and Olaf decided to camp, the rain had been unrelenting since lunch and we were all a little glum from the monotony of the road. Rose and I opted to push into the forest, expecting that tomorrow would be challenging enough and any extra headway made today would be a boon. Entering the forest the climb begins immediately. We were slowed by the mud and several large downed trees but made steady progress toward the peek, the mist thickening as we gained elevation. By the time we called stop the mist was thick around us and we cleared a barely-big-enough patch to pitch the tent and begin the process of drying off and warming up. Discovering that we still had phone service, I called home to England to bring ma up to speed on our travels.

Day 7 – No shortage of mud

After breakfast we lay in wait for a break in the rain, so as to strike camp with a minimum of misery. Outside the tent the cold morning mist crept underneath our clothes. The track was reduced to a brown river, punctuated by roots and deep pools of mud. A couple hours slog brought us to a hilltop weather station that Kath had mentioned as a suitable camp spot where we took shelter under a couple of solar panels and tucked into some scroggin.

As we put away our snacks and stepped out from beneath the panels we walked headlong into a very tall, grinning Irishman, who introduced himself as Paul. He was dressed for the downpour in a swish, bright red rain jacket and dark green hiking trousers, making my $5, second hand, broken zipped, paper thin ’rain jacket’ look rather pathetic indeed. Paul fell into step behind us, all of us glad of a little company and diversion in the grim weather. Mitch and Olaf must have leapfrogged us during our break because before long we came upon them ahead of us, trying to figure which way the track was headed. Rose set us straight again.

Owing to its notoriety, Raetea forest is one of only a few trails that has a numbered marker every kilometre. In our minds of course, each kilometre felt like two and we often cursed the time it would take before another would appear, in the worst section taking almost an hour to get between markers, but on the whole they were a welcome and rewarding sight. A few of the markers were adorned with messages of encouragement scrawled by other hikers:

At least you’re not on the beach anymore! — Dave, 10 Jan 2020

Some were less enthusiastic: “what a load of bollocks”, many repetitions of “WTF!”.

By lunchtime the weather had let up and the forest brightened as the clouds receded, allowing us to shed the grim plodding that had reigned through the rain. Though everything underfoot remained a slurry that tried with every step to pull our shoes from our feet, we were at least able to appreciate the beauty of the native bush that enveloped us. The ferns at our feet and the Ponga (tree-ferns) overhead, spread themselves out wide, their brilliant green obscuring the earth and sky both. Towai trees stretched out in every direction and, way above, a canopy created by magnificent kauri trees. The supplejack, that had so far seemed nothing but a nuisance… was still just a nuisance, but at least it wasn’t raining anymore.

The last couple of kilometres were easier still, as mud gave way to harder clay, more treacherous in terms of falling on your arse but not nearly as slow going. When we burst out onto a hill, looking out over a green valley beneath blue skies, the pleasure of the view was magnified by the relief of escaping the claustrophobic now confines of the forest. The five of us sat for a while, our wet clothes laid out to dry. All that remained was to walk a further two kilometres, across paddocks and along farm track, to a campground set up for trail walkers by a local farmer.

Making camp alongside Paul, Mitch, and Olaf that evening offered up the first opportunity for that wonderful past-time of observing other people’s routines. It was with respect to cooking that we differed most. Paul had his nifty little JetBoil, that brought water roaring to the boil for the purposes of re-hydrating his assortment of Backcountry Cuisine meals. Rose and I, for whom the thought (and expense!) of de-hydrated ready-meals was a non-starter, saw the walk as an opportunity to try and make trail food as interesting as possible given the implicit constraints. We carried fresh vegetables, made miso broth with rice noodles, seaweed, and shiitake mushrooms, and tried always to create meals that we would gladly put on the table at home. Mitch and Olaf each cooked separately. Olaf in particular proved himself an eccentric trail cook, firing up his burner, freely flinging anything and everything edible into the pot, and stupefying the rest of us by using as much gas in a single evenings cooking as we might in a week. Of course, every one of us would evolve and iterate on our dietary routines as the walk progressed, but each person’s trail-food philosophy would remain largely consistent with how it began.

Mitch’s phone – which had gotten very wet in a pouch he thought was waterproof – was dead, the first casualty of the walk. Olaf’s phone was not functioning either, but did ultimately recover.

The farmer came by later that evening, a man of a great many stories and very few teeth, who charmed us with stories of his varied possum trapping escapades, notable visitors to his camp in previous years and rivalries between himself and other local farmers, mostly to do with hunting, trespassing, and shooting each other’s dogs.

Day 8 – Appledam via Mangamuka

Owing to it being sighted directly beside a large stream, the campsite was as wet and cold in the morning as if it had been raining through the night. We set off without sight or sound of our compatriots and met the road to Mangamuka.

The road aggravated a pain in my knee and a tightness in my left thigh that had begun in the forest and were now making themselves known with every step. After little more than an hours walking we paused at the dairy in Mangamuka and despite the early hour the fryer was on and we breakfasted on the best hot chips New Zealand had yet provided this chip loving Brit, and for a mere $2.50!

I want to emphasize that these were legitimately amazing chips, not simply tastier on account of our exertions. It would be nearly a month and many hundreds of kilometres before we found a more Platonic ideal of the cooked potato in the famous hand cut chips of Golden Kiwi Takeaways in Taumarunui. Until then, Mangamuka dairy reigned supreme in our hearts and we spread word of their quality to all who would listen.

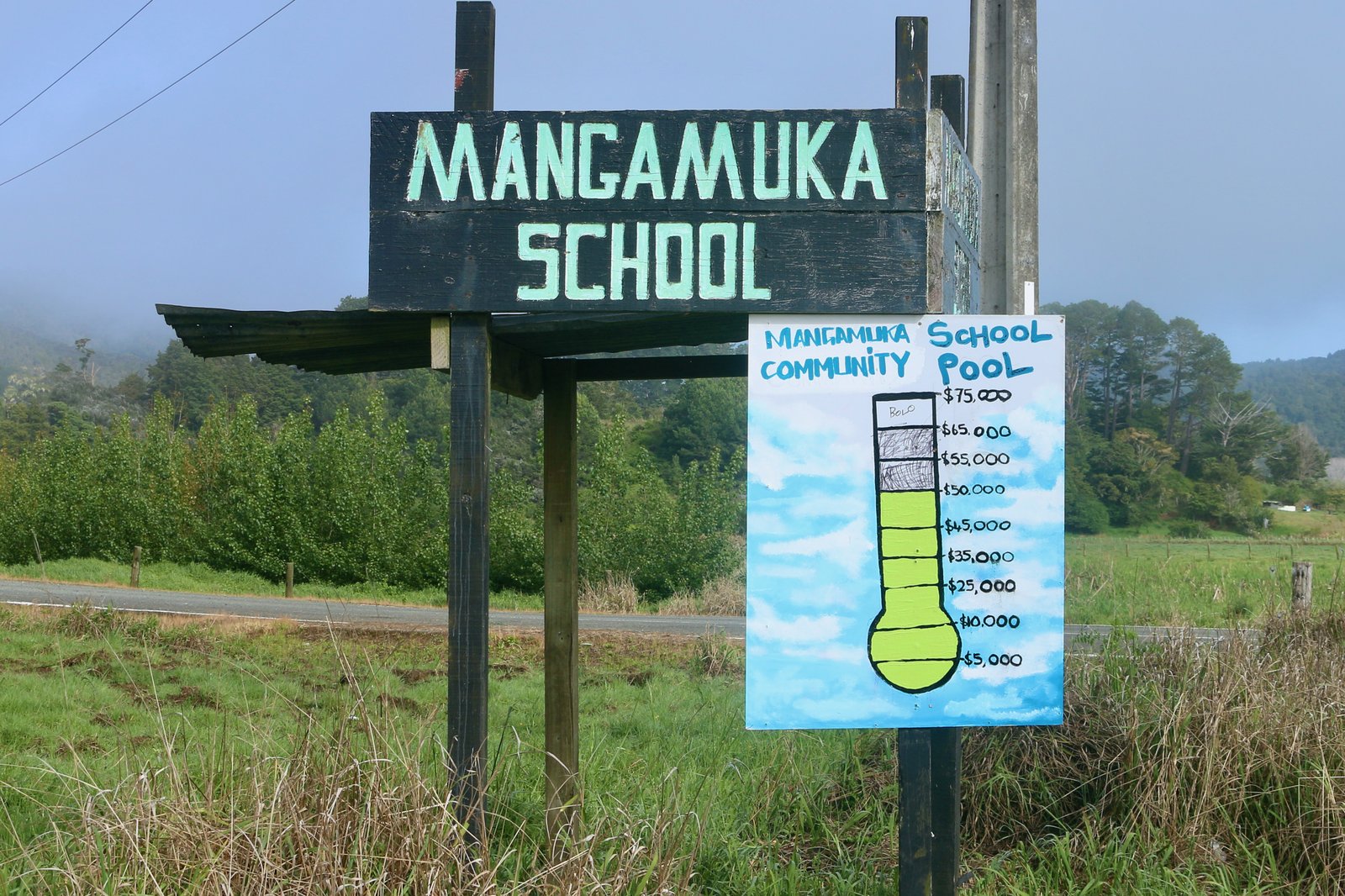

Walking the road to Mangamuka solidified my feelings about the value of trekking all the road sections of Te Araroa too. Along the way we saw signs erected by farmers protesting the rising controversy surrounding their livelihood; a charmingly painted thermometer depicting the progress of the local school’s fundraiser for the construction of a community pool; and a series of simple DIY bus stops at the road end of rural farming stations so that children waiting for the school bus could shelter from the elements. Glimpses of ordinary life that give shape, definition, and context to a journey.

The day turned – from cold and wet, to clear and bright, to hot and sticky – and we progressively removed layers. As Rose changed into shorts I was reminded just how hard small things can become on a journey like this, particularly at the beginning of one, before the body and mind have reached a situational steady-state. Every joint creaks, putting any weight on an un-shoed foot is painful, some things take twice or ten times as long as they would at any other time, as often as not simply for lack of a table or flat surface to work at.

We reached the Appledam campground in the Omahuta forest by early afternoon – about 20 kilometres from the days start – and had it to ourselves for a couple of hours, selecting the sunniest pitch, laying out everything that hadn’t fully dried since Raetea and picking our way down to the stream to cool our heels. Rose had struggled to keep going as the gravel of the forestry road continued to tenderise our feet and we exchanged foot massages and soothed ourselves with chocolate. I tried mending a slow bleed in my air mattress. I had already put up with it during the final month of my cycling trip around Australia, and – having been too lazy to fix it in the interim, failing to completely fix it at Appledam, and on other occasions later in the walk – that slow bleed that meant I was sleeping more or less on the ground by morning would persist for the full length of Te Araroa. Oh well, I tried.

Paul was next to arrive and as he put up his tent, we fell into one of the many gear conversations that the trail would provide. His gear was universally hi-tech, lightweight, and all new for the trail. Ours by contrast was low-tech, heavy, and almost entirely second-hand. Our tents provided very similar amounts of internal space, plus his had far larger vestibules in which to shelter his gear, but where Paul’s tent weighed barely 1kg, ours was a hefty 3kg. While the prospect of dropping two kilograms from the weight of my pack was appealing, the thought of spending more than a thousand New Zealand dollars to do so was not. Besides, I dislike buying things new, there’s plenty of stuff in the world already. Regardless, talking gear with Paul was very enjoyable, we both saw the merit in each other’s approach and could speak freely about the shortcomings of our various bits of kit.

With a big heart, a big stride, and a bigger mouth, Paul was easy to get along with and would become our closest and most enduring trail companion. By the end of that night, having expressed that I wanted to return to working outdoors post-trail, he had about convinced me to go and work for him on his apple orchard in Riwaka after we finished the trail.

I did go and work for Paul, driving a tractor on the orchards for six weeks of the harvest and my currently living in Nelson, the top of the south, is due in no small part to that invitation.

Paul told us Olaf had suffered a rough night, unbeknownst to us he had slept inside his emergency blanket, his sleeping bag having been soaked through in the rain of the previous day. By late afternoon there was still no sign of the pair and as evening dawned and deepened our curiosity became concern, but having no means of contacting them there was little we could do.

Day 9 – Appledam to Puketī

When we woke, we were heartened to see a pair of tents – one green, one orange – had appeared on the other side of the clearing. Mitch and Olaf had made it, though at what hour of the night it was impossible to say. Rose and I packed up quietly so as not to wake them and retraced our steps the kilometre back to the track.

At the border between Omahuta and Puketī forests we came across our first bio-security cleaning station, a simple unmanned checkpoint where trampers are asked to thoroughly clean their shoes and anything that may be carrying soil. Kauri die-back, a soil-borne disease, threatens the native Kauri forests of New Zealand. The only means of preventing it’s spread is to ensure contaminated soil is not carried between forests on shoes, through diligence on the part of all who recreate in the forests, and closure of forests when it’s spread has been identified.

After thoroughly cleaning our shoes we began a steep and slippy descent toward the Mangapa river, part way down we stopped to whip up our breakfast of porridge, sultanas, and peanut butter. Neither of us took much pleasure in eating immediately after waking up, eating first after an hour or two of walking proved much more enjoyable and we stuck to that mode just about everyday after. En route we startled a wild boar hiding out beneath a large fern and watched as it bolted across the track and disappeared back into the undergrowth. The track and the river become one at this point, and for five kilometres we waded through the cool water, crossing between the banks to avoid the deepest parts.

Paul caught up to us just as we were looking for where the track resumed, the water having become too deep to continue wading. Together we took a look at the map, backtracked just a little, and clambered up the bank back onto the track. Half an hour later I found myself wedged in a creek – bracing my legs against its far side to avoid dropping into the water below – having lost my footing on a deceptively slick and steep patch of clay. I felt vindicated in my folly when Paul, inching down the slope towards me, fell and ended up wedged right along side me. Tossing his pack and poles safely ahead of him, and with a foothold from me, he was able to clamber out the far side just in time for Rose – who was manoeuvring to take a photo of my predicament – to also lose her footing and come crashing into me. In the end, after we dislodged Rose, I opted to render my own rescue and levered myself out of the crevice.

In the third photo above you can see Paul looking back at the unassuming clay slide that assailed us each in turn.

The stretch of track that followed presented many such treacherous slopes, and short sharp climbs to match, in which Rose and Paul chorused that I was mad for not carrying walking poles.

Walking poles divide hikers. Those who use them swear by them, those who don’t swear them off. For my part, though I don’t have any interest in owning walking poles myself, I fully acknowledge their utility for some hikers. Rose used walking poles for virtually every inch of Te Araroa and there were numerous obstacles that would have been impassable or dramatically more dangerous for her without them.

After the zig-zag, up-down, slip-and-slide section came the up-and-up, lots-of-steps, like-really-a-lot-of-steps section. Paul had heard about the steps from another hiker who was a few days ahead of us and passed on the warning that they weren’t to be underestimated, so we all promptly stopped for lunch before making the attempt.

The steps didn’t disappoint. I was sceptical – I mean, surely steps should be

easier going than no steps? – but sure enough, the steps were a thorough work

out. Paul took the lead and after a time we stopped trying to keep up as he took

DOC’s notorious, awkwardly spaced steps two at a time. Rose finished her water

and mine on the way up, and when the grade began to level and the stairway to

heaven more stairs finally gave up it’s last flight we had but a short

scrabble through an overgrown section of track to contend with before we emerged

onto Pirau Ridge. From there it was a further nine kilometres along a four-wheel

drive track to Puketī camp, which on paper sounded nice and easy, except the

road had been recently re-surfaced in fist-sized chunks of gravel. Their size

meant almost every step ended up bridging between two such rocks, putting

immense strain on the arch of the foot. We very quickly wished the steps had

continued instead. By the time we reached camp a little before 7pm, our feet

were as tender as they had been at the end of the beach.

In a repeat of the previous night, Mitch and Olaf were still nowhere to be seen when Rose and I wriggled into our sleeping bags, but thankfully I did overhear them come trudging into camp before drifting off.

Day 10 – Puketī to Kerikeri through fields of green

To everyone’s surprise, Mitch and Olaf were up bright and early in the morning. After suffering through that god-awful road surfaced with boulders in the pitch black, their head-torches having run flat, brought almost to the point of tears by the pain and not knowing how far they had still to go until they stumbled into camp, they were resolved to setting off earlier in the mornings.

Paul had been the first up, but his routine of two morning coffees with a cigarette in-between, and drying his tent fully of the morning dew before packing it away meant that we four set off without him, knowing full well that his long stride would close the distance in no time.

The final day to Kerikeri was pretty pedestrian compared to the previous three. An easy walk across brilliant green farm land, bracketed by stretches of road walking, and finishing off with a walking path that would take us into town via Rainbow Falls. In no particular hurry, we strolled along, getting to know each other better. They were a decidedly creative pair, Mitch an aspiring rapper, Olaf a keen painter, both amateur film makers. Olaf produced a film camera and wandered off in search of something to inspire his painting, while Mitch filled us in on a raucous sounding reality show they had shot one summer.

Exiting the green fields on to a farm road we were met by a pair of eager pups who tailed us to the boundary to make sure we weren’t up to any mischief, while the purest white pigeon perched on a power line overhead, and Paul could now be seen gaining on us, though still distant. He caught us as we marched along the sealed road towards the Kerikeri river and we sat down to snack a little, nurse our tender feet, and call ahead to a hostel in town and see if they had room for the five of us – they did. As we neared the river, the boys fell behind, their blisters too inflamed to keep pace with Paul, who was flying towards the pizza he’d been dreaming about since Kaitaia. We kept pace, I was craving fresh fruit, Rose wanted a shower.

The path along the river was easy walking and we made good time in getting to the falls, which were grander than I had expected. From there it was only another forty minutes walk to the hostel. A little after 3pm, three of us all but fell into Hone Heke Lodge. We were met by the owner, a British expat who generously offered a discounted rate to Te Araroa walkers. After receiving the tour we were raring and ready to do absolutely nothing, Rose and I flopped into bed while Paul went in search of his prized pizza. The resupply could wait a while.

The journey from Kaitaia to Kerikeri took us 5 days:

- Day 6: 25.7km Kaitaia to Raetea

- Day 7: 15.8km Raetea forest

- Day 8: 19.3km Farmer’s camp to Appledam

- Day 9: 27.5km Appledam to Puketī campsite

- Day 10: 26.5km Puketī to Kerikeri

115 kilometres in all, bringing our total distance walked since leaving Cape Reinga to 241 kilometres. A daily average of 24km’s. But such numbers capture nothing of the mud!