The origins of the bug in the machine, Thomas Edison, Capt. Grace Hopper

I wasn’t quite satisfied with my recall of the first computer bug story when I told it recently, but it took me a while to piece together where I’d heard it. Eventually I got to thinking it might have been from Grace Hopper so did a bit more digging and turned up a video of a presentation she gave in 1982,

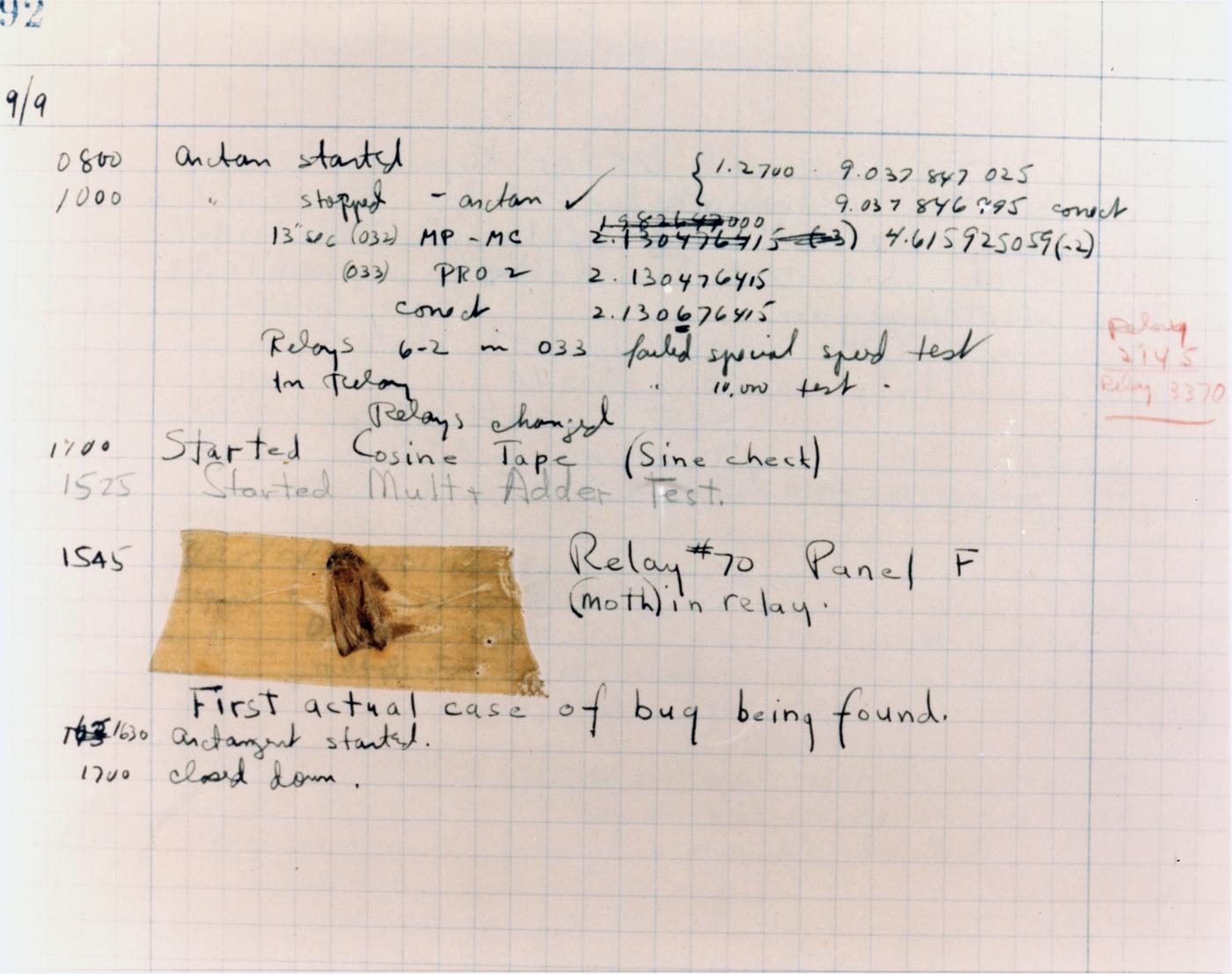

I thought you might like to know that the first computer bug is still in existence. We were building Mark II the summer of 1945. It was a hot summer in Cambridge, and naturally since it was World War II we were working in a World War I temporary building. Air conditioning wasn’t very good, no screens, and Mark II stopped. We finally located the failing relay, it was one of the big signal relays, and inside the relay, beaten to death by the relay contacts, was a moth about this big.

So the operator got a pair of tweezers and very carefully fished the moth out of the relay, put it in the log book, and put scotch tape over it. And below it he wrote, “first actual bug found”.

I knew you’d be glad to know that the bug is still in the log book under the scotch tape. It’s in the museum at the Naval Surface Weapons Center at Dahlgren, Virginia.

Which confirms what I had thought except for one significant detail: they were called bugs even before the finding of the bug.

The Wikipedia history of the bug cites Moth in the machine: Debugging the origins of ‘bug’ from Computerworld, September 3, 2011, and says,

The Middle English word bugge is the basis for the terms bugbear and bugaboo as terms used for a monster.

While a Thomas Edison quote confirms that Bug has been used to refer to undesired behaviour in a system since at least the 1870’s,

It has been just so in all of my inventions. The first step is an intuition, and comes with a burst, then difficulties arise—this thing gives out and [it is] then that “Bugs”—as such little faults and difficulties are called—show themselves and months of intense watching, study and labor are requisite before commercial success or failure is certainly reached.