General purpose, not always fit for purpose

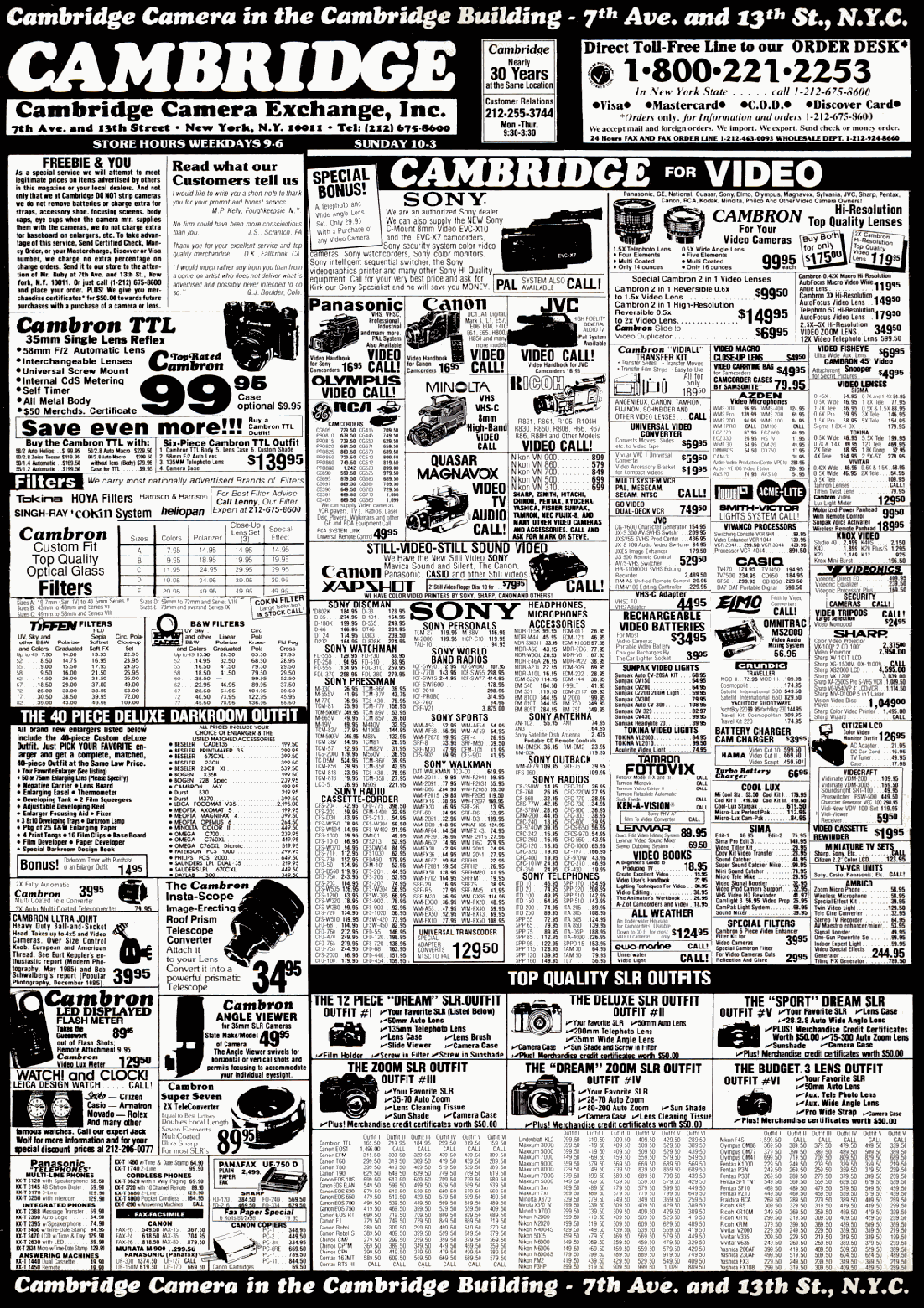

Look at this catalogue. In it’s midst is a section called ‘Sony Personals’, within you’ll find a long list of Sony Walkman models ranging in price from $19.95 to $619.95.

At the beginning of April, 1992 there were at least 51 different models of Sony Walkman players for sale. That alone seems extraordinary. I want to look at just one of them though.

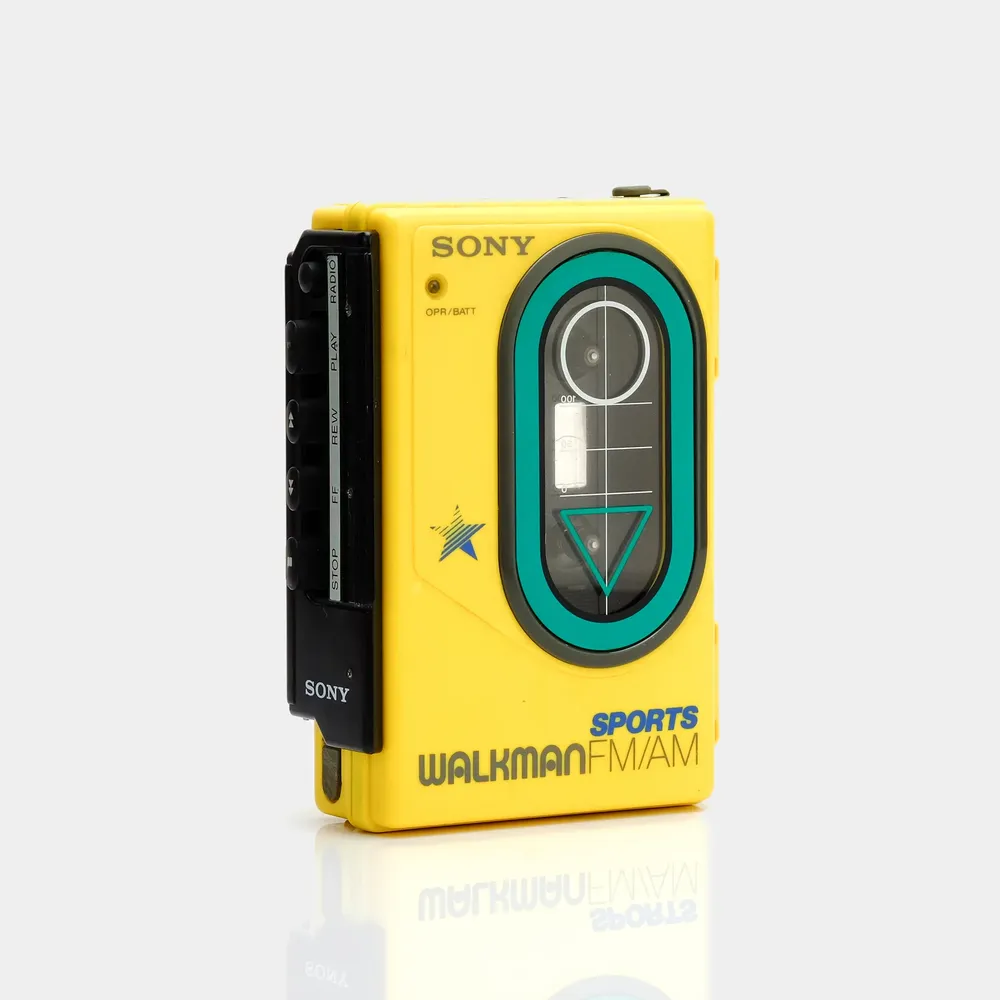

Released in 1986, the first thing you notice about the Sony Walkman WM-F45 is that it’s bright heckin’ yellow. Remember when things had colour? Of course, fashion moves in cycles and colour is making a comeback, smartphones have graduated from the Model-T Ford school of “any colour that you want, so long as it’s black” to now offering all sorts of garish finishes. But that’s not what I’m really talking about, there’s a lot more to design than colour.

The WM-F45 exemplifies a marriage of form and function that typifies good industrial design. It is just large enough for the interface, the control logic, and the single cassette tape it must house.

I find it strikingly beautiful too. It went on sale 4 years after Blade Runner (1982) released to the world, and it could just as easily be of that world. Utilitarian, solid, tactile, a little plexi-glass window through which to watch the action. Brightly coloured, stylised, accented, like an inanimate Pixar character. It is a beautiful artefact, like Snow White’s Coffin, the Braun SK4 Phonosuper. Released 30 years before the WM-F45, it exemplifies many of the same principles of form and tactility. Much like the Walkman that came after, the SK4 stripped away all that was unnecessary. The Phonosuper was notable for being substantially smaller than it’s contemporary counterparts. Cheaper, smaller, more iconic. The Phonosuper and the Walkman both make a home in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and for good reason.

But I don’t just want to talk about beauty, I want to use the Walkman as a lens for thinking about how our relationship to the objects we covet has changed. Trust and tactility have been eroded, replaced with distraction both.

Remember those tactile switches that things used to have? We called them buttons, I think. You pressed them and something happened, and you never doubted that the something would happen, because with their tactile response they assured you that the something would happen. Gone are the days where the something always happens. Now we tap a glowing widget on the cold slab of our pocket supercomputers, and we get put in a queue behind all the other garbage it’s churning through. We’re in a queue while our phones continue to download more images of cats we don’t know, or tee up another auto-playing advertisement tailored to us and our wallets by some bastard who we also don’t know.

The WM-F45 has buttons yes, and room for a cassette tape, but there’s much more to it even than that. Or rather there isn’t, and that’s the point. The WM-F45 doesn’t know how to do anything except what you want it to do. It is explicitly single-purpose, it plays music. It can play, pause, rewind, and fast-forward a magnetic cassette tape – and only one! – and it can tune into the radio. That’s it! It can’t read your emails, check the weather, unlock your door, or call you a cab. You can’t read anything from it or write anything to it. The only way you can ‘share’ what you’re listening to is to pull its fabulous orange-foam-padded headphones from your head and place them on someone else’s. It has one purpose, to play the music you like, wherever you like, and it is suited to that purpose.

In this age of abundance many of us grew up being told we could do anything, be

anyone. “This has made a lot of people very angry existentially

despondent and been widely regarded as a bad move”. But now we’ve done the same

with our objects. By converging on general purpose computers, heralding them as

a universal solution to all our tasks and woes, and putting them at the centre

of our lives, we have lost scope, lost sight of the edges of their purpose, as

we have lost sight of our own.

Maybe we can set up a simple litmus test for this: If an objects purpose cannot be described in a single sensible sentence, it might be too bloody complicated. And maybe, if we can’t put our own purpose into words either, then it’s because we have made our lives too complicated too.

Be like the walkman.

Or don’t, because this might just be nostalgia wank. And worse, it’s nostalgia for something that I remain complicit in the killing of, I carry a general purpose gizmo most everywhere. We need a word for that, a combination of hypocrisy and nostalgia. I write this to open a loop about the possible peril of general purpose devices, of generalising everywhere, of generalising everyone, and it does that, it opens the loop, but it doesn’t do much more than that. Maybe I’ll write more on this in the future, because as much as I love looking at beautiful objects, this isn’t really about industrial design.